The Blue Castle is the story of Valancy Stirling and her transformation from a brown-frocked spinster to modern lover. At first glance what appears to be a simple and uncomplicated romance offers fertile ground for contemplation.

The first sentence states, "If it had not rained on a certain May morning Valancy Stirling's whole life would have been entirely different." This preoccupation with fate is explored throughout the novel. To what degree is the path of our lives determined by mere chance, how much is preordained and what role does free will play? A humourous but socially marginalised character challenges church doctrine on predestination and his argument prevails over those of the theologians. Just so, the protagonist Valancy questions the validity of her status as a member of the "elect," as a daughter of the well-respected Stirling family. She throws off the shackles of her birthright, a status confirmed on her not by merit or effort but by chance, and consciously choses her own path to self-fulfillment. Free will here is for the courageous visionaries. It is a new world order we see envisioned in The Blue Castle, and it is the brave, those undaunted by fear who are able to transform themselves through their own efforts and live in freedom and happiness.

Valancy's favourite author, the naturalist philospher John Foster gives us the overarching theme of the novel: "'Fear is the original sin,' wrote John Foster. 'Almost all the evil in the world has its origin in the fact that some one is afraid of something.'" Most of the characters are ruled by fear; "What will people think?" dictates every behaviour of the dour Stirling clan: it is the wagging finger of the church leader, and the gossip of the townsfolk. Fear has dictated the rules of belief and behaviour that make life a prison for those who abide.

L. M. Montgomery allows us to see what happens when a character is given the opportunity to cast off the fear that keeps her confined. A natural lifestyle is equated to a modern one, and all that is traditional and established is equated with outdated, passionless, stagnant, disease-causing artificiality. In the fantasy world free from society's artificial constraints, clothes are valued for their comfort, food is simple and nourishing, sleep comes in a rhythm that matches the needs of the body, there is a connection to the land that is entirely lacking in society, and the needs of the emotional life are fully met. The psychological interior and exterior appearance begins to meld and the emotions break through the shell of social contraint. When this happens, social regulations strictly delineating class structure become meaningless. The true measure of a human is no longer the superficial attributes of wealth, social position, family name or appearance. It's a wonderful fantasy! And L. M. Montgomery places before us a projection of what could be possible if one were brave enough to take the reigns of one's own life, to cast off all that is unnatural, staid and conventional, to live a utopian existence where all emotional needs are met.

Of course, I am always fascinated by fictional character who struggle with illness, and Valancy Stirling is an interesting case. Diagnosed at the beginning of the story with a fatal heart ailment, Valancy is given a year to live. The illness narrative itself is merely a plot device, and not of nearly as much interest as the real psychological ramifications of the diagnosis. The mind can create its own cure when it is deprived of its natural nourishment, and Valancy has created a place of peace, comfort, and escape in her imaginary blue castle. L. M. Montgomery addresses both the cause, but also the remedy for this psychologically distressing lifestyle where, trapped in a world where creativity is stifled, solitude forbidden, novels strictly disallowed, the mind finds its own healing. One senses that Valancy's retreat to this internal world of fantasy and of books is something L. M. Montgomery wrote straight from her heart. This internal world served to fulfill all her basic emotional needs and soothed her soul until Valancy was able to manifest her heart's desire in reality. When her reality was offering her all the emotional support she needed, her fantasy world was no longer needed - her inner and outer lives had merged.

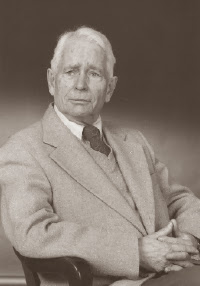

| Lucy Maud Montgomery |

I know that The Blue Castle is one of L. M. Montgomery's quietly popular books after the Anne and Emily series. I loved the descriptions of the Muskoka region of Ontario, of the contrast between the musty Stirlings and the moonlight canoe trips. The darkness that often lurks just below the surface in L. M. Montgomery's writing is here; she does not shy away from social ills and uncomfortable topics such as illegitimate children, alcoholism, depression, illness, bullying, death, neglect, hypocrisy. There is a constant undercurrent of negativity, but it is counter-balanced by her overwhelming optimism. The old will die away, and the new world will bloom, reborn. The new ruling religion is based not on the rules of the past but on love and joy in nature. The "shock of joy" is the birth pang of a new life, but the resurrection is not dogmatic, but firmly grounded in the pleasure of earthly joys.

.jpg)